BioUnfold #5 — AI in Drug Discovery, or the Art of Dealing with Noise

In the previous post, we discussed why AI needs biology literacy. There is perhaps no better illustration than how we deal with noise.

In biology, signal and noise are never separate. Every experiment contains uncertainty — from pipetting to microscopy to sequencing. The art is not to eliminate noise entirely, but to understand it well enough that learning can still emerge.

Broadly, there are three families of strategies to handle noise:

- Collect more data — brute-force your way through variance.

- Curate the data — identify and correct specific artefacts.

- Model the noise — formalize uncertainty in the learning process.

We will look at each briefly, then focus on curation — where most discovery teams spend their time.

1. More data — the brute-force approach

Getting more data is often the easiest answer, and it works — up to a point.

In one screening pipeline I co-developed, we trained and validated models within a single experiment. The models never generalized beyond that screen, but that was acceptable. The goal was not a universal predictor — it was to extract the most value from this experiment.

This is a recurring theme in drug discovery: local validity beats global ambition.

A model that helps one project move forward can be more valuable than one that generalizes to none.

Still, even brute force depends on disciplined curation.

2. Data curation — the universal step

No matter how much data we collect, biological experiments demand cleanup.

Curation has two main styles:

- Understanding the system — addressing each source of noise directly.

In imaging, for example, we correct illumination gradients, plate drift, and batch effects due to handling. - Post-hoc normalization — applying statistical methods to reduce variability once data are aggregated.

In practice, both often combine. Each assay type — imaging, transcriptomics, proteomics — has its own noise patterns and its own correction family.

A note on chemistry

In chemistry, noise rarely takes the form of batch artefacts — it comes from measurement scarcity. Each compound brings dozens of readouts — potency, permeability, solubility, logD — and every one must be right for a lead to advance.

Unlike imaging or omics, there are few global correction methods. The defense is redundancy: multiple orthogonal assays and careful cross-validation of predictions.

Here, AI’s role is not just denoising but triaging uncertainty — helping chemists decide which measurements are trustworthy enough to act on.

3. Statistical modeling — the deeper layer

The most demanding approach is to model noise explicitly.

This means designing mathematical structures that represent not only the signal, but the uncertainty around it.

Such models can generalize from small datasets precisely because they expect noise.

They bridge the gap between data analysis and simulation — the first step toward reliable in-silico experimentation.

But this requires deep understanding of how experimental noise behaves — biologically and statistically.

From principle to practice

These ideas only come alive when tested on data.

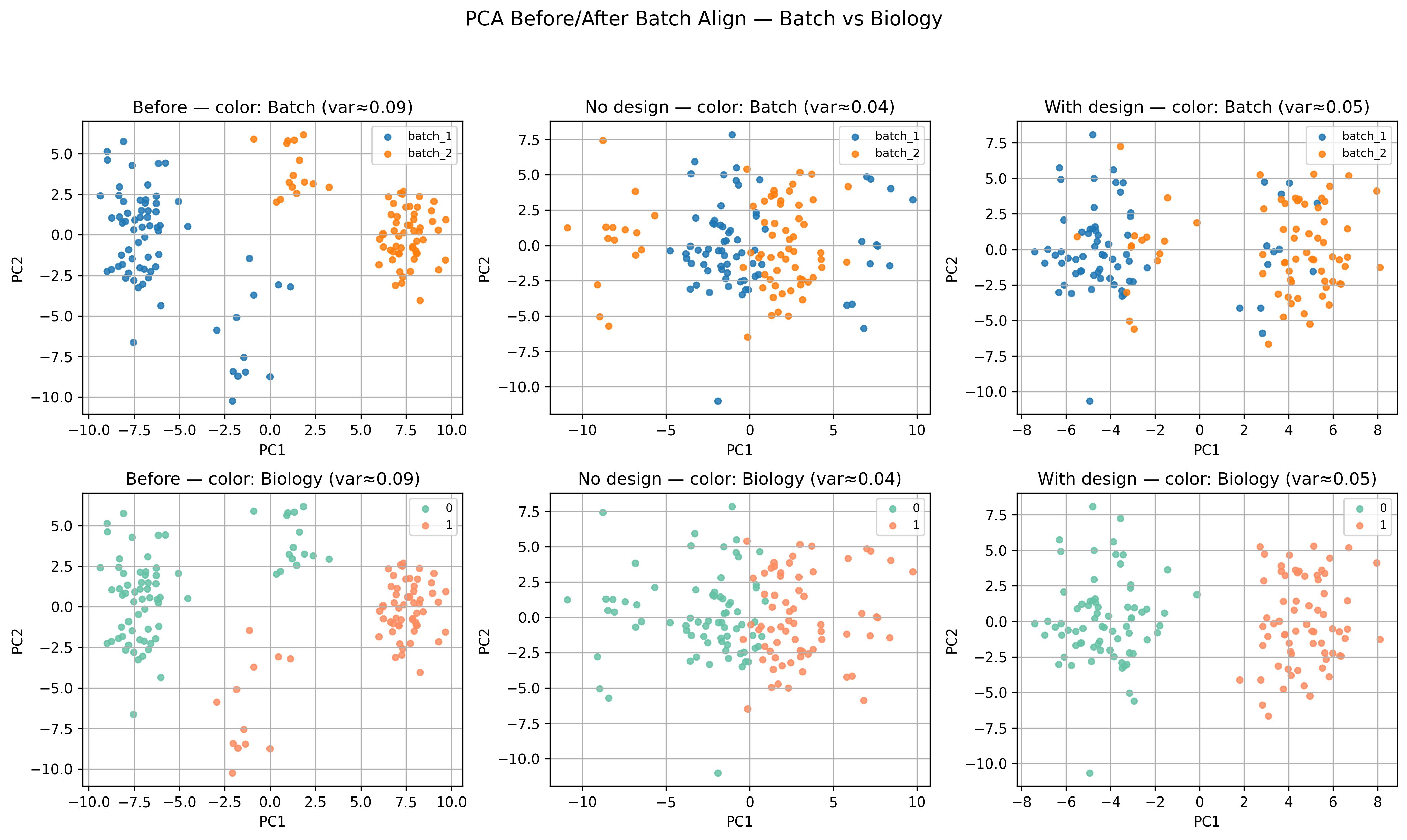

In the companion notebook, we explore a simple but powerful approach to batch correction:

- Batch Align, which adjusts mean and variance across batches while preserving biological signal.

It is a last-step correction, not a substitute for good experimental design — but it shows how statistical reasoning and biological context work together.

You do not need large datasets to follow along; the goal is to see how biological intuition shapes technical choices.

→ Companion notebook

Closing thought

Dealing with noise is not a side quest in AI-driven discovery — it is the quest.

Noise tells us what we do not yet understand about the system.

Managing it is where modeling meets measurement — and where progress depends on curiosity shared between biologists and AI experts alike.