BioUnfold #8 — Choosing the Right Foundation for Biology

In the last two years, foundation model has become a default aspiration. Every field wants its own. In biology, that often means retraining a large architecture on internal data, hoping it will generalize better to new experiments.

That can be valuable — but not always.

The decision to train a foundation model is less about ambition and more about fit:

what problem are you trying to solve, and what is missing from the models that already exist?

Two Kinds of Motivation

Teams usually start such projects for one of two reasons:

- Better methods — they believe the architecture, loss, or training scheme can outperform current baselines.

- Better data — they have access to information that others do not, and want to capture its structure.

The first case is applied research. It can produce incremental gains, but rarely creates lasting advantage unless you publish and maintain it. The second case — data — is where foundation models truly matter. But it is also where risk is highest.

Assessing the Data Case

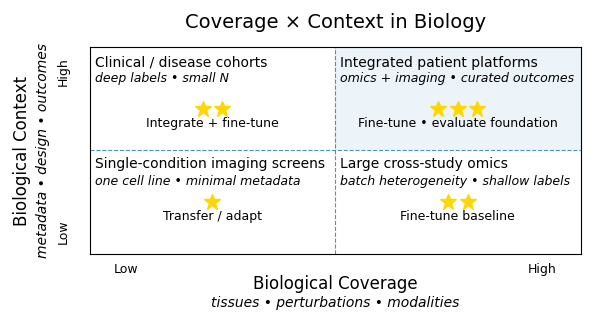

A foundation model only helps if your data add coverage or context that general models have not seen.

Coverage means new biological regimes: a rare organism, a novel assay, or an unstudied disease area.

Context means richer annotation — repeated or aligned observations that reveal relationships others could not learn.

In omics, this pattern is becoming clear. Public repositories already capture much of the accessible space, and large open models trained on them perform well. The advantage now comes from contextual depth — hospital partnerships, disease-specific cohorts, longitudinal samples. These datasets do not replace foundation models; they extend them, grounding predictions in real patient biology.

In cell imaging, particularly immunofluorescence, the trajectory is less certain. Models pre-trained on generic natural images transfer surprisingly well. Specialized IF encoders show published gains, but adoption remains limited. The constraint is often not model architecture but label balance, staining variation, and how images relate to underlying biology. A hybrid approach — combining general visual knowledge with biological calibration — may prove more effective than training from scratch.

The Real Cost

Training is rarely the expensive part. The real cost is preparation — not just cleaning data, but defining what “a valid signal” means.

For biological datasets, this includes building assay taxonomies, handling outliers, aligning supervised and self-supervised objectives, and agreeing on evaluation metrics.

What counts as success? A mechanism of action recovered? Potency correctly ranked?

The model depends on decisions made long before training begins.

If early experiments do not show clear improvements, confidence in the approach erodes quickly.

That questioning is healthy, but it consumes time and compute budget. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence — yet every project needs a line where exploration stops.

In discovery, stopping is not failure — it is part of the experiment.

Budgets often treat compute as variable, and staff time as fixed. In practice, both are scarce. Fine-tuning may cost a few thousand dollars a week; full training can reach six figures. These are not small costs relative to a small team’s capacity to explore.

A Subtle Trap

Owning a foundation model can feel like owning an advantage. In practice, the advantage fades unless the model evolves with new experiments and validation data. Biological data are rarely abundant or uniform — screens, replicates, and conditions keep changing. A model stays useful only if it stays grounded in that reality.

The sustainable advantage is not the model itself but the infrastructure that connects assays, curation, and retraining.

In practice, the decision often follows a simple rule:

If your data expand biological coverage, a foundation model can make sense;

if they refine quality or context, smaller models or fine-tuning are usually enough;

if they only narrow the scope, integration and interpretation are the better path.

In Practice

Before starting such an effort, three questions help clarify intent:

- What problem are we solving that current models cannot?

- How much unique signal does our data really contain?

- How will we know that the effort succeeded — beyond loss curves?

In omics, the frontier is integration — making models that connect public data with private, well-annotated patient slices. In imaging, it may be label design — capturing biological meaning more faithfully than current encoders do.

In the end, foundation models are a means to organize biological knowledge. Their value depends less on scale than on how well that knowledge connects back to experiment.

Foundation models are useful when they expand the range of biology we can represent, not just the size of the model.