BioUnfold #9 — Target Identification in Motion

Target identification has always been both the starting point of discovery and its final constraint.

It defines what success looks like — yet it often begins with incomplete knowledge.

Traditionally, it meant finding a biomolecule to modulate: a receptor, enzyme, or gene central to disease. In practice, “target identification” spans a spectrum — from pinpointing a single protein to defining intervention points at the pathway, cell-state, or tissue-interaction level.

Today, AI and large-scale data are shifting what “a target” can be — and how we judge that it matters.

The Two Pillars of Target Evidence

A convincing target rests on two forms of evidence:

mechanistic understanding — knowing how a molecule contributes to a biological process — and dynamic context, understanding how it behaves: its half-life, localization, and variability across cells or disease states.

AI is helping both. Mechanistic links are now inferred not only from literature and pathway maps but also from graph-based models that integrate omics, imaging, and phenotypic data. Dynamic context increasingly comes from single-cell and spatial datasets, where AI can align heterogeneous signals into coherent patterns.

What used to be a static hypothesis (“this protein drives X”) becomes a living model of biological behavior.

Three Modern Approaches

Most programs combine three complementary routes to finding and defining targets.

Literature-driven discovery mines existing knowledge to set the field of hypotheses and map known mechanisms. It is the natural starting point — defining the biological boundaries within which models can learn meaningfully.

Data-driven modeling integrates public and proprietary datasets to infer causal or associative networks. AI expands the search space and identifies where intervention might have leverage.

Perturbation-led discovery uses CRISPR, siRNA, or phenotypic screens to uncover mechanisms directly from experiment. Despite being labeled “unbiased,” these approaches still depend on context: you need a well-chosen biological system and measurable outputs to translate hits into dynamic understanding.

Target identification is an exploratory exercise — it can absorb infinite time and money if left unbounded. The most effective programs plan it along that axis: defining how much exploration is enough, and how results will be translated into downstream work.

The most forward teams treat these not as alternatives but as feedback loops.

Literature defines the topology, models generate hypotheses, experiments test them, and data refine the next iteration.

What Makes a Good Target

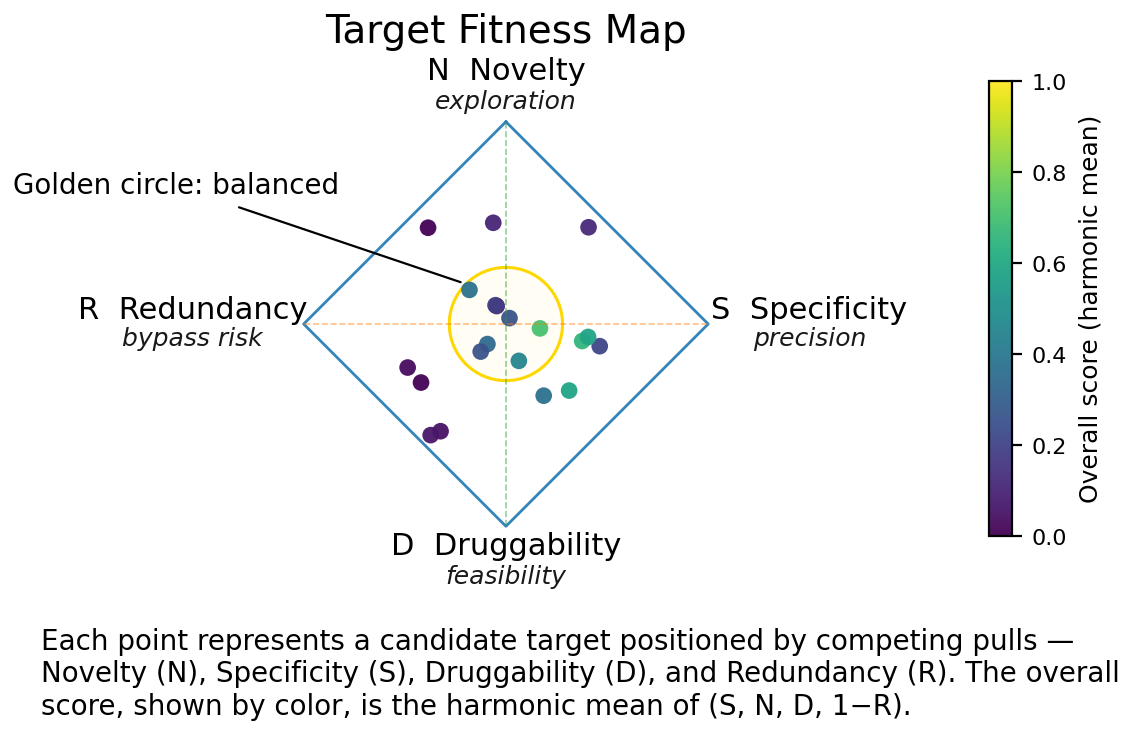

AI can suggest hundreds of plausible leads. Strategy is about filtering them. A strong target typically balances specificity (it affects the intended pathway more than others), redundancy (its function is not easily bypassed), druggability (it can be modulated by a molecule or biologic), and novelty (it opens unexplored biological or competitive space).

AI helps quantify these dimensions — predicting binding surfaces, causal dependencies, and network centrality. Yet biological judgment remains decisive: a model can rank importance, but only a biologist can judge viability.

AI also helps with characterization and quantification. In phenotypic data, characterization distinguishes whether condition A is meaningfully different from B; quantification measures how much and in which direction. In target identification, characterization dominates — but without reliable quantification, separation may be illusory.

The scale of such work varies widely. A CRISPR screen may probe thousands of genes, while a high-content imaging campaign can cover hundreds of thousands of conditions. The data footprint grows faster than the interpretability, which is exactly where AI can help extract structure without losing meaning.

The New Possibilities

AI is not just speeding up discovery; it is expanding what counts as a target.

Spatial and single-cell integration now reveals multicellular interactions — for instance, communication between tumor and stromal cells — as potential intervention points. Multimodal embeddings link disease signatures to subcellular localization or protein complexes. Foundation models learn abstract “axes of vulnerability” — not just molecules, but states worth modulating.

This reframes target identification from a search problem to a mapping one. Instead of asking “which molecule causes this disease,” we now ask “where in the system can intervention most effectively reshape biology?”

Where Biology Still Leads

Not every new target originates from computation. Often, it begins with a biological re-interpretation — a new way of describing how cells organize or malfunction.

For example, work on biomolecular condensates reframed diseases once defined by single proteins into problems of phase-separated systems — membraneless compartments whose formation or dissolution affects transcription, signaling, or stress response.

Here, the hypothesis is biological, but AI helps define it: analyzing imaging, sequence, and perturbation data to identify which condensate components are causal, which are contextual, and which are noise.

Similarly, the rise of complex assays — co-cultures, organoids, on-chip systems — reflects a biological push toward more realistic models. These systems increase biological relevance but also data complexity, demanding AI to extract interpretable structure. In that sense, biology increases relevance; AI restores readability.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, model-first or simulation-driven discovery reverses the flow:

AI defines a plausible mechanism, and experiments test whether it exists.

Each direction — biology-first or model-first — is valid.

The future of target identification likely lies in the dialogue between the two — a dialogue that rarely happens inside a single organization. It happens through the literature — one group’s biology becoming another’s model, and vice versa.

Planning from the End

Target identification is the first step of discovery, but it should be planned from the end.

Your screening, assays, and validation workflows will determine which targets are actionable.

A receptor matters only if your modality can reach it.

A condensate matters only if your system can measure its dynamics.

The best programs define their target strategy and data strategy together — designing experiments that both answer biological questions and create reusable, model-ready knowledge.

The new frontier of target identification is not finding new molecules — it is discovering new ways biology can be made actionable.

Discovery begins with imagination — and survives through definition.