BioUnfold #11 — Hit Discovery: From Diagnosis to Prediction

Hit discovery is the moment when biology, chemistry, and computation finally meet the first actionable signal of a discovery program. It condenses everything that came before — assay design, optimization, and QC — into a single question:

Which molecules do something meaningful to the system?

It is also where the workflow shifts from exploratory interpretation to repeatable interpretation. Most of the signal now behaves as expected, and the remaining anomalies surface in the narrow band where biology still surprises you. This transition is what makes hit discovery such an energizing milestone: measurement becomes testable signal, and the program produces its first actionable biological effects.

A Foundation Built Upstream

By the time a team reaches hit discovery, its assay has already been strengthened through repeated testing. Biomarkers are stable, controls are known, preprocessing is standardized, and the pipeline has matured into a predictable sequence of steps.

Hit discovery depends completely on live QC. Dispense artefacts, illumination imbalance, plate movement, focus drift, or staining decay all appear in real screens and cannot be corrected afterward. Catching these issues requires streaming data, QC checks embedded within the run, clear repetition criteria, and a culture where repeating plates is normal. If a program never repeats a plate, its QC is almost certainly insufficient.

A quieter failure mode appears when QC is partial. Biologists tend to spot biological artefacts while computational teams spot statistical or imaging artefacts; each sees different failure modes. Reliable hit discovery emerges only when QC criteria are jointly owned, agreed upon, and applied consistently across teams. QC is not a final gate — it is part of the experimental design.

In a well-tuned system, 95 percent of the plate behaves normally. The remaining 5 percent of outliers — unexpected drifts, subtle shifts, inconsistent wells — are not failure modes; they are where interpretation matters.

Choosing the Right Representation

Whether a team uses classification or clustering, the quality of the representation — the feature space describing each perturbation — often matters more than the choice of algorithm. This representation should be tested during assay optimization, not improvised during hit discovery.

In practice, teams rely on:

- Feature-based profiles, such as CellProfiler or handcrafted morphological descriptors

- Lightweight deep-learning embeddings, often CNNs or PCA-compressed representations

- Pretrained encoders, such as DeepProfiler or DINO-style models fine-tuned to IF or HCI data

- Foundation-scale encoders, but generally only if they were built for previous programs — there is rarely time to train one mid-campaign

As discussed in BioUnfold #8, representational choices are not about model ambition but about biological fidelity and reproducibility.

Four Ways to Call Hits

Because different methods surface different kinds of biological response, most teams combine several complementary approaches. Together, these four routes map the full range of what a screen can reveal: amplitude, separability, structure, and model-guided exploration.

-

Single-Feature Scoring

The simplest and most common approach is to derive hits from a primary biomarker, often calibrated by Z-prime and controlled thresholds. In transcription-factor assays, this biomarker might be nuclear intensity. In fibrosis models, it may be cell eccentricity — a single geometric descriptor that captures the phenotype surprisingly well. This method is fast and interpretable, but blind to composite or emergent signals that unfold only in multidimensional space. -

Classifier-Based Scoring

A classifier can separate positive and negative controls and becomes significantly more robust when tool compounds are included to anchor mechanism diversity. However, these models are sensitive to drift and depend heavily on the stability of the controls — exactly why drift analysis and control characterization must be handled during assay optimization. Thinking backward is essential: classifier reliability at hit discovery is determined by decisions made much earlier. -

Unsupervised Clustering

Clustering reveals families of perturbations, rare responders, and context-dependent phenotypes. It excels in prioritizing follow-up work when biology is complex or multidimensional. High-dimensional structure can be difficult to interpret, but when the representation is stable, clustering provides a view of the system that single-feature or classifier outputs cannot match. -

Active Learning

Active learning closes the loop between computation and experiment: the model proposes the next conditions, and the lab tests them. It succeeds only when experiment and computation move at the same pace. Earlier in discovery, these disciplines often drift out of sync, but by hit discovery — with stable assays, defined controls, and clear signals — the conditions finally exist for adaptive loops to contribute real value.

Although much of the public conversation around hit discovery focuses on imaging and phenotypic screens, the principles apply equally to biochemical and binding assays. In those modalities, hits emerge through quantitative shifts: affinity changes, kinetic constants, or inhibition curves. Clustering and diversity prioritization will typically occur on a chemical embedding space. Yet the underlying logic remains the same: trustworthy signal, strong QC, stable representation, and clearly defined hit criteria.

The Economics of a Screen

Phenotypic hit rates of 1–2 percent are common. Screens are noisy, assay windows vary, and follow-up capacity is limited. Many programs reserve a fixed secondary assay budget, and hit discovery becomes the funnel that fills it.

To reduce downstream cost, teams often insert a short “confirmation layer” between primary and secondary assays — for example, running a small set of compounds in triplicate to remove artefacts before committing to more intensive work. This simple step can dramatically reduce false positives and prevent waste in validation campaigns.

From Discovery to Direction

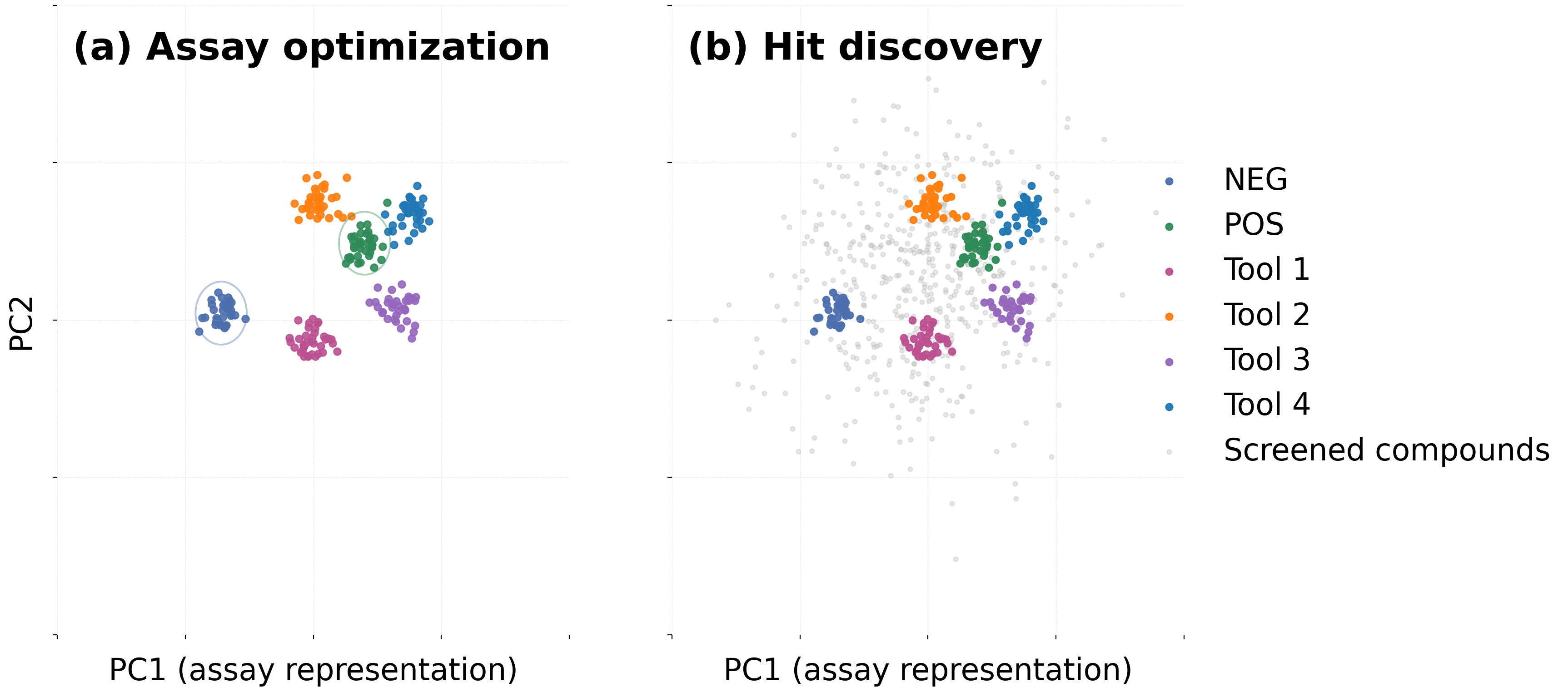

During assay optimization, AI is primarily diagnostic: quantifying separability, drift, illumination stability, and consistency across replicates. At hit discovery, AI becomes predictive: ranking hits, surfacing subtle responders, and identifying which perturbations are strong candidates for validation.

This transition works only when experiment and computation operate at a shared pace. By hit discovery, the biology is stable, the assay is tuned, the representation is known, and the pipeline is repeatable — the necessary alignment for AI-driven prioritization to have practical value. When both disciplines finally move together, hit discovery becomes not a bottleneck but a multiplier, turning raw screens into signals that the entire discovery engine can build upon.