BioUnfold #12 — Lead Optimization: Learning the Chemistry

Lead optimization is where discovery becomes engineering. It is the careful process of turning an active molecule — often unstable, imperfect, and biologically complex — into something that can survive the full environment of the body.

In BioUnfold #7, I wrote about how AI can help chemists think beyond binding and optimize the whole molecule. Here, the focus is not on the property space itself but on the process: how learning and chemistry interact inside the DMTA loop.

From Hit Discovery to Lead Optimization

At the end of Hit Discovery, teams typically emerge with several dozen active molecules across a range of chemotypes. Some chemotypes produce a small constellation of variants, while others appear as singletons — molecules that show activity but offer no immediate structure–activity relationship. Once singletons, artefacts, and unstable actives are removed, most programs begin lead optimization with a few dozen viable starting points.

These molecules are rarely “drug-like.” They show potency, but little else is tuned. Some bind cleanly; some behave inconsistently across assays; others depend on context that is not yet understood. But they represent the first concrete evidence that the biology can be modulated. Lead optimization begins by taking these early signals and asking a more ambitious question:

How do we turn a biologically active molecule into a viable therapeutic candidate?

During hit discovery, success meant “find signal.”

During lead optimization, success means “shape that signal into something that works in a living system.”

DMTA: A Learning System Hidden in Plain Sight

DMTA — Design, Make, Test, Analyze — is both a workflow and a feedback system. Each iteration teaches the team what improves the molecule and what the system will not tolerate.

- Design — Chemists propose modifications that nudge one or two properties toward the desired profile.

- Make — The molecule is synthesized, constrained by cost, feasibility, and synthetic accessibility.

- Test — The compound is evaluated in biochemical, cellular, ADME, or safety assays.

- Analyze — Data reshape hypotheses and determine the next properties to improve.

Even without AI, DMTA is a closed-loop learning process. With AI, it becomes explicit: the model proposes hypotheses, experiments validate them, and the system updates. But this only works if the process is structured to enable learning at the same pace as the chemistry.

Pricing and Speed: The Real Constraints of DMTA

A reality rarely discussed publicly is that DMTA is constrained less by algorithms and more by synthesis cost and assay throughput.

- A generative model might suggest 500 promising molecules, but the chemistry team can make 10–20 per cycle.

- A binding assay might support 1,000 measurements per week, while a cell-based assay may support 100.

- Multi-parameter optimization is shaped not just by the biology, but by what the team can test, at what price, and how often.

A good DMTA pipeline treats model output not as “the molecules to make,” but as ranked hypotheses competing for scarce experimental capital.

Thin Data, Practical Constraints, and the Need for Discipline

At the start of lead optimization, teams often have fewer than twenty analogs per chemotype with measured activity. Structure–activity relationships are faint. Data are noisy. Models cannot yet distinguish signal from artefact — not because they are weak, but because the biology has not expressed its shape.

Assay strategy widens this gap:

- Biochemical binding assays provide a direct, mechanistic readout of target engagement (Kd, Ki, IC₅₀). Their key advantage is not just speed, but that the signal is relatively clean and unambiguous. In favourable cases, computational models trained on consistent binding data can approach the reproducibility of the assay itself. Once this alignment is established, the model can safely pre-filter large design spaces, dramatically accelerating which molecules are even considered for synthesis.

- Cell-based assays are slower and more resource-intensive, but capture permeability, metabolism, polypharmacology, and emergent cellular mechanisms. They become essential when the mechanism is incomplete, multiple targets are likely to matter, or the therapeutic effect only appears in a cellular context.

Most programs therefore combine both: the binding assay provides reliable signal and a calibration target for models, while the cell assay provides biological truth. Together, they define the early DMTA cadence as much as any chemistry decision.

Models Must Move at the Pace of Chemistry

One of the quietest but most damaging failure modes in AI-driven chemistry is model staleness. If a model is trained on data from two cycles ago, it proposes molecules aligned with old priorities. Chemistry and assay realities move forward; the model points backward.

To avoid this, the model must be:

- Lightweight enough to update every cycle

- Able to learn from small batches

- Equipped with uncertainty estimates that prevent overconfident hallucinations

- Conditioned on shifting project priorities, not static property targets

When models update at the same cadence as experiments, DMTA becomes a coherent learning loop rather than a parallel track.

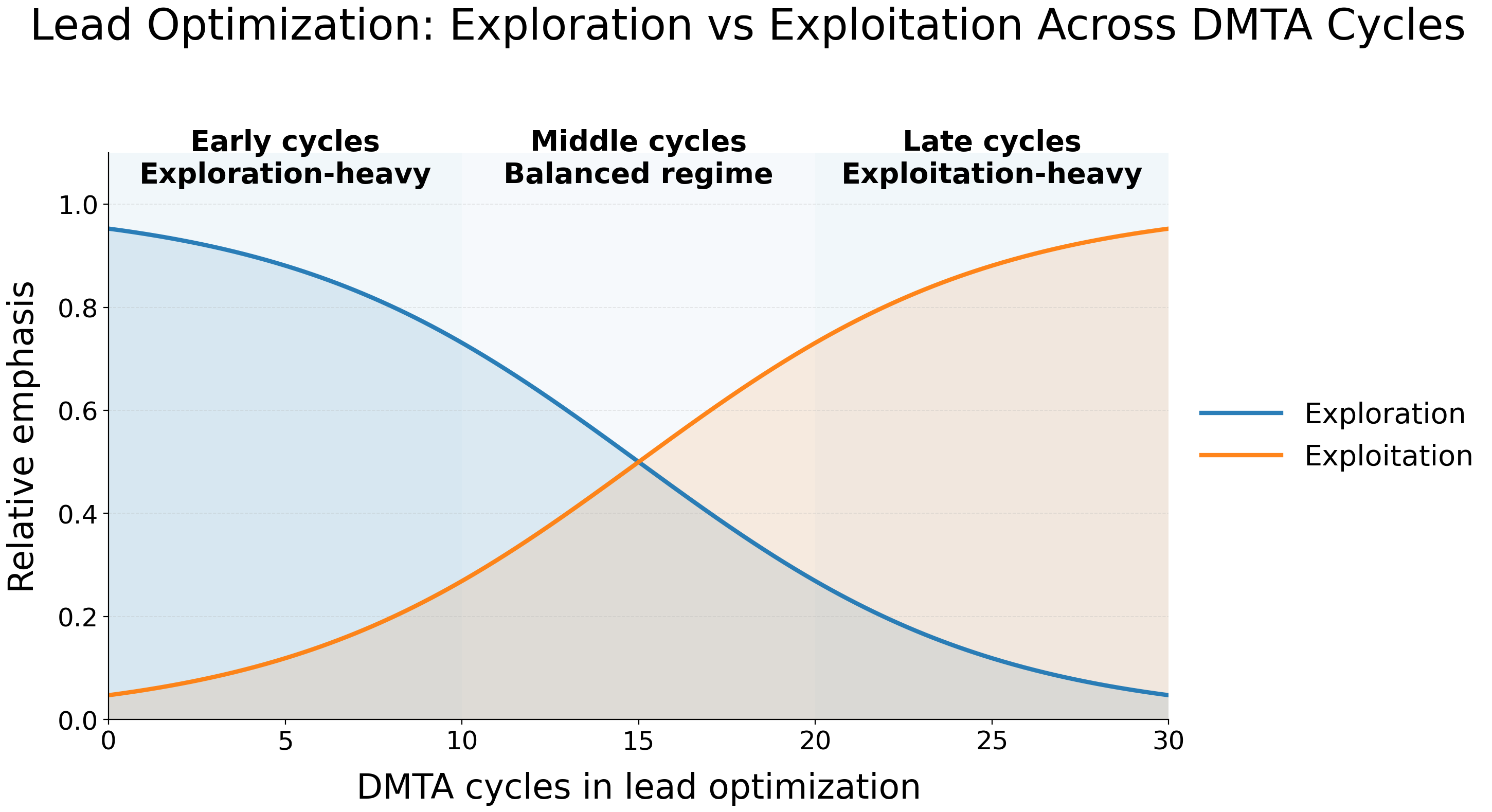

Exploration vs. Exploitation Across the DMTA Lifecycle

Not all cycles are equal:

Early cycles

- Favor exploration

- Allow larger structural jumps

- Accept low probability of success for high information gain

- Focus on mapping constraints, not refining potency

In the earliest cycles, the priority is to apply project-specific static filters (Ro5 heuristics, aromatic ring limits, solubility thresholds, toxicophore removal), because very little data is available.

As the cycle progresses, these filters become more sophisticated as the team begins to understand what the biology will accept.

Middle cycles

- Integrate model guidance

- Explore trade-offs (potency vs solubility, permeability vs clearance)

- Balance risk and tractability

Once enough data accumulates, a generative model can be trained.

The model should be modulable, allowing team priorities to become explicit inputs that steer the search process.

Late cycles

- Prioritize exploitation

- Make smaller, controlled changes

- Focus on PK, safety, stability, and developability

- Use generative models to refine, not reinvent

A healthy DMTA system implicitly has a temperature parameter — high in the early phase, cooling as decisions become more constrained.

Most AI pipelines ignore this progression, generating excessive novelty late in programs or over-exploiting too early, leading to misalignment between model behaviour and chemical feasibility.

Bridging the Tempo Gap Between Chemistry and Data Science

A recurring challenge in real programs is that computational and chemical workflows operate on different tempos. Chemistry advances according to synthesis queues and assay turnaround times. Data science advances based on clean inputs, feature stability, and model retraining cycles.

When these rhythms diverge, insights often land after decisions have been made — not because chemists resist AI, and not because data scientists lag, but because the process does not define when the model should influence the decision.

The solution is to align roles explicitly:

- Chemists articulate the specific property trade-offs that matter in this cycle.

- Data scientists tune models to deliver timely, relevant proposals within those constraints.

- Both sides agree which decisions are model-informed and which are chemistry-led.

When this alignment is present, AI becomes a directional tool. When it is absent, AI becomes commentary.

From Iteration to Direction

Lead optimization can feel incremental — cycle after cycle, small adjustments, gradual improvements. Yet it is also the stage where the feedback structure between design, experiment, and analysis becomes visible.

The model proposes.

The lab tests.

The system learns.

And slowly, the molecule becomes a candidate.

What elevates a program is not the sophistication of the algorithm, but the architecture of the loop. When computation and experiment move together, DMTA becomes more than a workflow: it becomes a directional engine capable of guiding a molecule toward the clinic with speed, coherence, and scientific realism.